Welcome to Agreeable Instantiations Volume 2: Random Permutations, Symmetric Group Action and The Dovetail Shuffle. In this week’s post I hope to share interesting information about the dovetail shuffle and its validity as a permutation representation defining symmetric group action.

My first introduction to this topic was a result of thesis work completed for my graduation from the UCLA Master of Applied Statistics program in 2022. The title of my Masters thesis is Game Theoretical Solutions in Blackjack and Chess via Markov Decision Process Algorithmic Analysis. Much of the thesis is concerned with the development of a non-deterministic algorithm capable of playing discrete games; the thesis and its content are still available online for interested readers.

In the planning of the implementation of the Blackjack games, my advisor and I agreed that shuffling the deck after every round of play was the best way to approximate a fair pitch for the Markov process player(s) against the dealer. Without shuffling the deck after every round, the Markov process player was able to gain a >1% advantage against the dealer, while shuffling the deck after every round the Markov process player was able to limit loss to a <1% disadvantage against the dealer.

In the context of work completed in my thesis on Computerized Game Theoretical Markov Procedures, only the total value of the hand is parameterized by the Markov process and update procedure for optimization. The Markov process was not parameterized to remember specific cards in its hand however if the Markov process was parameterized to remember cards from information available in the partial or complete information variants of the Blackjack game, this would be the start of the consideration of the Markov process Blackjack solution as a card counting procedure. A true implementation of a card counting procedure would include the consideration of a memory of cards dealt in previous games, the number of previous games included in the memory is determined by the shuffling procedure. If the Markov process had been parameterized to have a card counting memory, it probably would have been able to further boost its performance above its 1% advantage in the versions of the game where the 52 card deck is shuffled less frequently.

Still, as I mentioned, it was agreed during my thesis that it would be best to limit attention to Blackjack games where the deck is shuffled after every round of play. This almost necessarily neutralizes the potency of card counting strategies and also reduced the Markov process player from a 1% advantage to a <1% disadvantage in 1-on-1 play against the dealer.

In shuffling the deck after every round, we are hoping to approximate a queue of an infinite number of shuffled decks. A successful card counting strategy is based on a memory of a certain number of games, and this number of games is effectively determined by how often the deck is shuffled, and also how many shuffled decks are in queue.

Of course, the implementation of shuffling procedures in the Blackjack game will require more advanced consideration of the queue of decks in order to avoid reshuffling in the middle of an ongoing round. For example, if a casino has a queue of 10 shuffled decks, and the first deck only has 3 cards left after a round of Blackjack, it may be wise to continue to the second deck in queue at the start of the next round of Blackjack. Similarly, in computer experiments, if the shuffled deck only has 3 cards left after a round of Blackjack, it may be wise to re-shuffle the deck before start of the next round of Blackjack. With such a procedure, we can hope to shuffle the deck frequently enough between rounds so that we never have to shuffle the deck during an ongoing round.

Without getting into an explicit calculation, an infinite number of decks would be prohibitive of any effective card counting memory. Somehow, the Blackjack games are more fair if we can approximate an infinite queue of decks—of course we cannot and do not want to shuffle the deck during any ongoing round, so the best we can do is shuffle the deck prior to every round in order to maximally mitigate the utility of card counting strategies. In a seemingly unrelated but importantly implicated note, the number of Blackjack players in addition to the dealer in a given round of Blackjack may be an interesting variable to investigate the impact of both card counting strategies and also the status of the deck during any ongoing round of Blackjack. Players near the bottom of the dealing order may have slightly different strategies based on how many players are in a given round and also how frequently the deck is shuffled between rounds.

**(Blackjack is understood to be a solved game, my thesis only hoped to explore the specific application of the Markov process as a solution to be optimized in a game-theoretical sense. But beyond the performance of any specific algorithm, I still wonder what is the basis of the dealer’s advantage in Blackjack. Now, I admit, I may want to return to the Markov player experiments in a future volume to include a card counting memory in some experiments and prohibit card counting memory in others. I am inclined to believe this may help interested individuals, myself included, to develop an understanding of what the basis of the dealers advantage is in Blackjack.)

***A search on the internet for sources about the degree to which Blackjack is a solved game may yield varied results. In my recent experience, there are sources that describe that there is an optimal pure strategy for the game of Blackjack, making it a solved game. Research from my thesis at UCLA did not consider the development of pure strategies as final solutions, and I am of the belief that this may be a compelling experimental goal and potentially insightful process to study in the future.

Results quoted from the aforementioned research concerning Game Theoretical Markov Processes are interesting, but today I am more interested in why and how the dovetail shuffle may find success in creating a fair pitch, which happens to be a foundation for the dealer’s potential advantage in Blackjack. When shuffling the deck after every round, if a riffle shuffle can approximately reproduce the deck as a uniform sample from one of the 52! permutations of itself, this is the best approximation to having an infinite number of decks in queue, where each deck is a uniform random sample of one of the 52! permutations of the symmetric group of order 52. To my understanding, such an arrangement is the maximally fair setup for a series of Blackjack card games, as player’s strategy performance is minimally dependent on the status of the deck as it is shuffled.

In the experimental implementation of my research on the topic of Computerized Game Theoretical Markov Procedures, I was able to implement a dovetail shuffle for the experimental computation of the strategy performance, and in the theoretical analysis I found valuable resources for understanding more about the statistical implications of the group theoretical permutation representation of symmetric group action.

The symmetric group of order 52, S52, is exactly the 52! permutations of the deck we wish to uniformly sample. Without getting too far ahead of myself, the symmetric group action is defined to be the mapping from one of any possible arrangement of the deck of cards with any valid permutation of that deck of cards, resulting to a final arrangement of the deck of cards.

If the group theory of symmetric group action can help us evaluate how the dovetail shuffle may approximate a uniform random sample of the symmetric group, this would be great. As a start to this conversation, an important idea is that the distribution of certain characteristics of the deck at one iteration of the dovetail shuffle and the next iteration of the dovetail shuffle can be monitored to check that they are similar to the characteristics expected of two decks drawn from a uniform random sample of the 52! permutations.

The discovery that there are statistical implications of the group theoretical permutation representation of symmetric group action was an exciting one for me, and I hope to continue inquiry into this subject matter. John Baez’s own published mathematical writings, research and papers did inspire this initial discovery for myself. I am often inspired and encouraged by many mathematical writings found on his blog(s) and online postings, as well as much of the other resources I can find on mathematical topics of interest via the internet. However, on this topic, the theory of Symmetric Group Action characterizing Random Permutations, I believe Baez has published much information which can contribute to a wonderful understanding of the topic.

I will refer to certain chapters from Baez’s series on Random Permutations, but the informative number of works from Baez on Random Permutations can be found here https://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/permutations/

Admittedly, I am not completely fluent in the language of group theory, so I will aim to keep it simple, but I will also source info from informative resources to develop as sharp a resolution as I can in writing this post.

By definition, the permutation representation that defines symmetric group action is a faithful group action. In contrast, the dovetail shuffle as a random process is a practical, computationally tractable implementation that can only hope to well approximate the symmetric group action defined by group theory, really there is no guarantee that the dovetail shuffle adheres to functional constraints implicated by the group theoretical definition of the permutation representation group homomorphism.

As I mentioned earlier, an important concept to consider is that two decks drawn at one iteration and the next iteration of the dovetail shuffle can be compared to check that characteristics of these decks are similar to that of the characteristics expected of two decks drawn from a uniform random sample of the 52! permutations. An important consequence of this is that eventually we would also like any two decks drawn from any two iterations of our dovetail shuffle to have the same joint distribution as any two decks drawn from a uniform random sample of the 52! permutations.

This consequence is the best way to reach the maximally fair, minimal deck status dependence shuffling policy in which cards are drawn from an infinite queue of shuffled decks. Also, this consequence is equivalent to saying that any number of multiple iterations of our chosen dovetail shuffle should be equivalent to a single iteration of our dovetail shuffle. If some forms of the dovetail shuffle can be identified as perfectly uniform, each individual iteration of these amenably formed shuffles should be independent.

For example, consider that the deterministic, perfect riffle shuffle is guaranteed to produce the identity permutation after every 8 consecutive iterations of the shuffle. This direct dependence contradicts the independence we hope to observe in the random process, but truthfully any deterministic shuffle will have an analogous set of contradicting dependencies. As a result, this deterministic perfect riffle shuffle does not adhere to our initial design constraint that any two iterations of our dovetail shuffle ought to be distributed as any two uniformly drawn random permutations. Importantly, it seems that the functional constraints implicated by the group theoretical definition of the permutation representation group can and should guide the design of a non-deterministic dovetail shuffle that may hope to well approximate a uniform random sample of the permutation group elements of symmetric group action.

In the series of Baez’s mathematical blog centrally concerned with Random Permutations, there are a number of interesting chapters with information for understanding what is meant when describing the joint distribution over any two decks drawn from any two iterations of a dovetail shuffle. A section of the analysis that stood out to me as I included it as a reference in my thesis is a question about the number of cycles above a certain size in any given permutation.

In the permutation representation of symmetric group action, a permutation representation can be characterized by its conjugacy classes, which are the cycle types of a permutation.

FYI/TMI it may be unclear if permutation is singular or plural, and it can be used so almost interchangeably, however I want to try to clarify that they are essentially the same because if I refer to a single permutation of order 52, you can assume that it was performed from the initialization of [1,2,3,4,5..52], however if I refer to two permutations, you can think that one single permutation action was performed on permutation one, in order to get permutation two.

This may also be an introduction to why it is important to think about the marginal distribution over permutation actions as a joint distribution of two permutations as well.

In other words:

Up to isomorphism of the cardinality of the set of size n with the integers up to n, there is only one way to write any one single symmetric group element.

[1,2,3,4,5..52]

However, there are multiple ways to write any one single permutation group element of symmetric group action.

One, we could write two symmetric group elements on top of each other, where digits in the top row move to the index of the digits in the bottom row.

[1,2,3,4,5..52] [1,2,3,4,5..52]

[1,2,3,4,5..52] [52..5,4,3,2,1]

Two, we could break the digits into distinct partitions, and order digits in the partition where each number moves to the index of the digit following it, leaving the last digit of the partition to move to the index of the first digit of the partition.

(1,2,3)(4)(5,31,50)(6)(7,20)…(41,52)

The representation of permutation group elements shown above is a correspondence to distinct composite cycle types of permutations.

For example, if a permutation can be represented by two consecutive copies of [1,2,3,4,5..52], or any two consecutive copies of the same ordering of 52 cards for that matter, there would be group theoretical implications of faithful symmetric group action. In the subjected case of two consecutive copies of the same ordering (i.e. permutation copy one = permutation copy two), this would be the consideration of the identity permutation group element of the symmetric group action. This identity element can be identified as the only element with 52 cycles in its cycle type, each cycle with only one element because this cycle type corresponds to the permutation group identity element represented by picking up each card and placing it back exactly in its same previous index in the deck.

For the purposes of considering the cycle types, it is convenient to think of distinct cycle types corresponding one-to-one with distinct permutation group elements of symmetric group action. In this way we can write two permutations next to each other and confirm that the permutation action is represented by separating the 52 digits into a number of disjoint non-empty distinct cycles/partitions, where digits belonging to a given cycle partition are exchanged only with members of that same partition. This gives us an interesting way to identify any given permutation action of the 52!.

Each cycle type of S52 symmetric group action is valid insofar as the cardinality of its constituent cycles sum to 52. There is one cycle type with 52 cycles, each with only 1 element. There are a number of cycle types with a number of cycles between 1 and 51 cycles, only valid representations of symmetric group action on 52 elements if the sum of elements in cycle type constituent cycles sum to 52 and the cycle type constituent cycles are disjoint partitions of the integers up to 52.

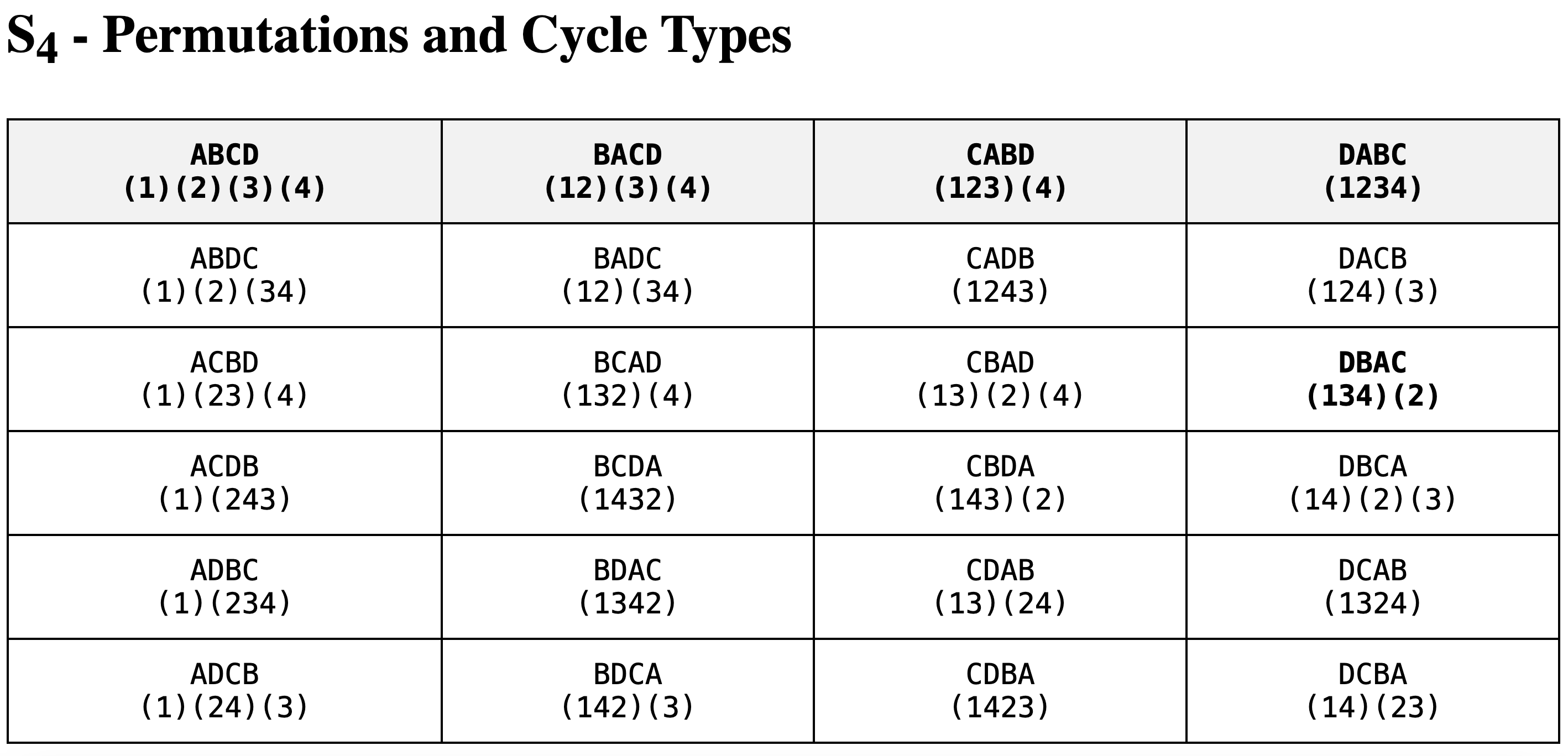

*Cycle types of S3 and S4 listed above to demonstrate symmetric group elements and cycle type decomposition corresponding to permutation group elements of symmetric group action. In the notation above, the permutation group action is considered by generating the permutation that maps to any given symmetric group element from the first symmetric group element listed (either ABC, or ABCD for S3 and S4, respectively). In this way, the cycle types (1)(2)(3) and (1)(2)(3)(4) correspond to the permutation group identity element. As another concrete example, for the ACB S3 symmetric group element, the (1)(23) cycle type decomposition corresponds to keeping A in its place as the first element (1) in ABC, and swapping B and C in their places as the second and third elements (23) in ABC.

As a proof left to myself and the reader, the conjugacy classes of the symmetric group correspond to its cycle types: two permutations are conjugate if and only if they consist of the same number of cycles of disjoint lengths. A piece of the proof lies in the fact that importantly, the identity element with 52 cycles in its cycle type is the only member of its conjugacy class, while all other conjugacy classes of the symmetric group have multiple members.

In understanding cycle types, here we first found that the identity element of S52 corresponds to the only cycle type with 52 cycles, each with only one element. This makes sense because in a uniform sample, we would want to draw the identity permutation in symmetric group action 1/52! times, and since there are 52! distinct cycle types (if we don’t ignore which digits go in which cycles, which we can’t in the case of 52 cards distinct by either number or suit), then the only cycle type with 52 cycles should only appear one time as the singular identity element of the permutation group: faithful symmetric group action.

In part 4 of the series on Random Permutations on his mathematical blog, Baez introduces the concept of a giant cycle as a cycle with size greater than n/2 or 52/2 = 26, in the case of the 52 card deck. With the introduction of the giant cycle, some facts about the occurrence of events in a process of uniformly random permutations become more evident. The first fact is that if one giant cycle appears in any given cycle type of a random permutation corresponding to a symmetric group action element then it is the only giant cycle that can appear in the given symmetric group action element. Clearly, since the sum of cycle sizes in a cycle type must be equal to n = 52 then if a giant cycle g > 26 appears, the total sum of remaining cycle sizes must be strictly less than < 26, meaning that even if there is only one remaining cycle after the appearance of a giant cycle, this cycle is necessarily not a giant cycle (there may be more than one remaining cycle, in fact, in expectation, there are, however these remaining cycles are necessarily not giant).

The facts about the appearance of giant cycles leads us to believe that only one giant cycle can appear in any given cycle type, and so we may then investigate the probability of the appearance of a giant cycle as a Bernoulli random variable supported by the random process of the dovetail shuffle. This investigation first starts with a question, best posed by Baez himself, “What is the probability that a randomly chosen permutation of n elements has a cycle of length > n/2?”. Given our understanding of giant cycles and the permutation representation of symmetric group action, we may form a hypothesis test underpinned by the computation of the sample expected value of the probability of the incidence of the appearance of giant cycles in a non-deterministic dovetail shuffle.

In its incredible use of theoretical evaluation and computational rigor, Baez’s work on Random Permutations shows that the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle of size k is (k)-1. As the occurrence of a giant cycle of any size is mutually exclusive, the occurrence of a giant cycle in the cycle type conjugation of a permutation corresponding to a symmetric group action element can be calculated as (n/2)-1 + ((n/2) + 1)-1 + ((n/2) + 2)-1 + ((n/2) + 3)-1 + … + ((n/2) + ((n/2)-1))-1 + (n)-1 which —> ln(n)-ln((n/2)) = ln(2) as n —> infty.

For the subjected case of S3 above we are interested in the permutation cycle type decompositions which have more than 3/2 = 1.5 or g>1.5. Similarly, for the subjected case of S4 we are interested in the permutation cycle type decompositions which have more than 4/2 = 2 or g>2. In other words, in S3 a giant cycle must have 2 or more elements and in S4 a giant cycle must have 3 or more elements. From the enumeration of S3 and S4 symmetric group permutation elements with their cycle type decompositions, we can confirm that the probability of a giant cycle in a uniform random sample of permutation group elements of S3 symmetric group action is 1/2 + 1/3 = 5/6 and similarly the probability of a giant cycle in a uniform random sample of permutation group elements of S4 symmetric group action is 1/3 + 1/4 = 7/12.

Thus, for a 52 card deck we can calculate that the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle is 1/27 + 1/28 + 1/29 + 1/30 + … + 1/52 = 0.683. If the dovetail shuffle implemented in the code for our Blackjack games is an unbiased estimator of a perfectly fair uniform shuffle of permutations of the deck, then the cycle types of the permutations applied by each iteration of the dovetail shuffle should produce samples whose empirical giant cycle occurrence probability tends toward the true value of 0.683.

Truthfully, there are even more sample and distributional characteristics that can be used to verify the validity of the dovetail shuffle as an unbiased and computationally tractable realization of the permutation representation of the symmetric group action, but the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle is a good start to a potential certification of the non-deterministic riffle shuffle as an unbiased estimator of a uniform random process.

In a later volume, I will explore how the occurrence of a cycle of any size, giant or not, may be checked, effectively matching the empirical distribution of cycle sizes of the dovetail shuffle to the expected distribution of cycle sizes of the symmetric group action in order to characterize the dovetail shuffle’s convergence in probability and distribution to that expected of the uniform distribution over symmetric group action elements, but still this is only for cycle sizes. I suspect I may revisit this subject in a future volume to consider the distribution of distinct composite cycle types on the whole, rather than only composite cycle sizes.

The code for the following experiments presented here was implemented using a non-deterministic dovetail shuffle. I will save some of the details of the implementation in code, but the dovetail shuffle implemented in experiments here takes 4 passes over the deck, each time splitting the deck into 2 or 4 blocks, and riffles the blocks back together, randomly selecting an element from the top, or bottom of the blocks. The code completing these 4 passes over the deck is implemented using a wrapper function prm(), which is meant to be a best approximation to a uniform selection of the permutation group action elements. For the purposes of independence and uniformity, we found that a non-deterministic shuffle was our best hope for an approximately uniform random process. As for the runtime of the non-deterministic shuffle, it seems that 4*n ~ O(n*logn) operations may be the best we can hope for the implementation of a shuffling procedure. Consider that producing a random element uniformly from the brute force enumeration would take O(log(n^n)) = O(n*logn) operations, so this seems to be a good milestone to hit. However, remember, we have yet to introduce the non-deterministic dovetail shuffle as an unbiased estimator of the uniform random sample.

So, how can we develop tests for bias and/or independence where samples hope to tend toward true expected values as iterations tend toward infinity?

The brute force enumeration will always be O(n^n), but a thoughtful hypothesis test of 1-10M samples should have a certain power. Confirmation of tendencies at infinity may be hard to capture experimentally, but finite empirical samples of the dovetail approximation should yield fitting acceptance regions in hypothesis tests of bias.

Consider a 1M uniform random sample of memory from brute force enumeration and random access with or without hashing would cost O(10^68) would be a lot harder than O(10^6*n*logn) ~ O(10^8) for a 1M sample dovetail shuffle hypothesis test.

The brute force method can effectively guarantee itself as a uniform random process, but if we do not necessarily know the size of the deck we are tasked with shuffling, the dovetail shuffle offers a compelling alternative, since there may not always be time to hash and/or enumerate all of the permutations prior to a request for a uniform sample.

Without an absolute guarantee of uniform independence of cycle types, we will test the bias of the dovetail shuffle with the empirical probability of occurrence of giant cycles. In today’s exercises we hope that the dovetail shuffle’s empirical giant cycle rate of occurrence sits in the acceptance region given by a two-sided Bernoulli hypothesis test. If there is time, I will try to comment on the behavior of the dovetail shuffle’s empirical giant cycle occurrence totals within a given acceptance region for various sample sizes.

The dovetail shuffle sampling and hypothesis testing for this week’s post was implemented with a Google CoLab Python Notebook, and I will include selections of code and resulting calculations from this notebook in order to present experimental results and hypothesis testing considerations.

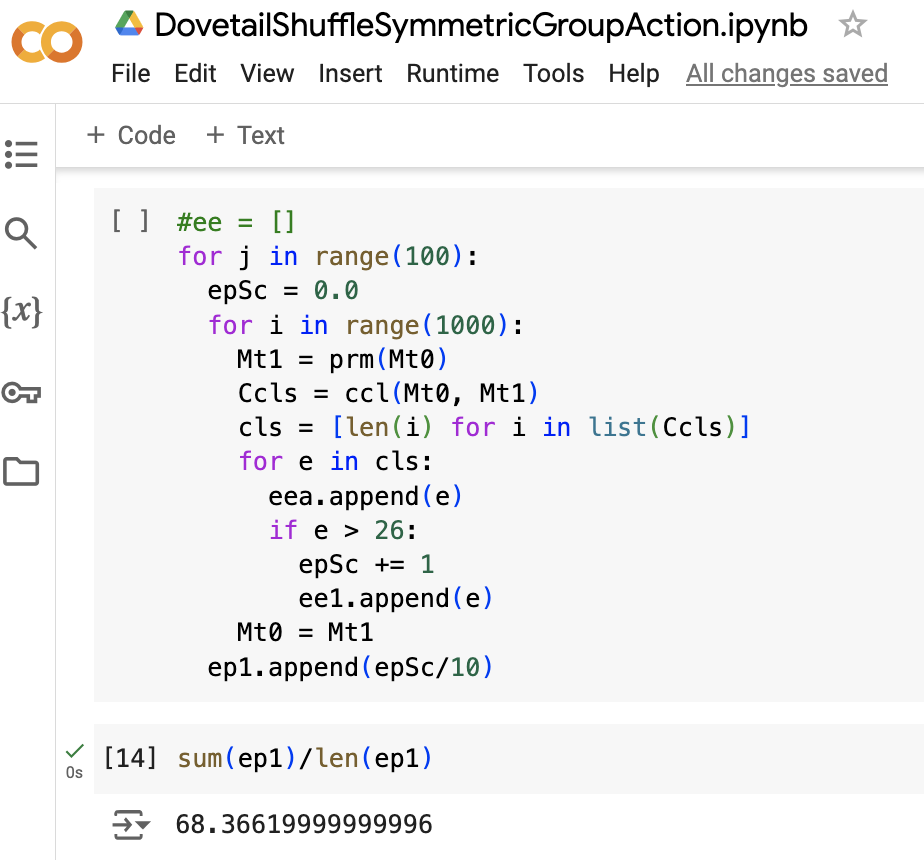

A 1M sample of the 4-pass dovetail shuffling procedure was used to evaluate certain sample statistics which hope to contribute to a discussion of the non-deterministic dovetail shuffle as an unbiased estimator of a uniform random sample of the permutation group elements of symmetric group action. There are a number of characteristics of the distribution of a uniform random sample of the permutation group elements of symmetric group action. Let’s refer to these relevant characteristics as the measure theoretical quantities of interest of random permutations.

As an aside, as much as I enjoy measure theory, once more, I am not yet fluent, however I want to add that for the purposes of the discussion in this week’s post, the measure we are interested in is the uniform random measure over permutations, and the quantities we are interested in are those associated with this measure which can be computed as implicated by their measure theoretical definitions, and which serve as null hypothesis true values for hypothesis tests of bias. In this way, the measure theoretical quantities of interest of random permutations provide a good base for a meta-hypothesis which asks whether a non-deterministic dovetail shuffle is an unbiased estimator of the uniform measure over permutations.

Importantly, this meta-hypothesis has a seemingly large number of sub-hypotheses which may investigate the occurrence of events as sample statistics estimating the true parameter of Bernoulli random variables. It may be difficult to answer the meta-hypothesis on the whole, but we can use the results of the experiment’s 1M sample of the dovetail shuffle to evaluate some of the relevant cycle compositional quantities of interest of the uniform measure over permutations.

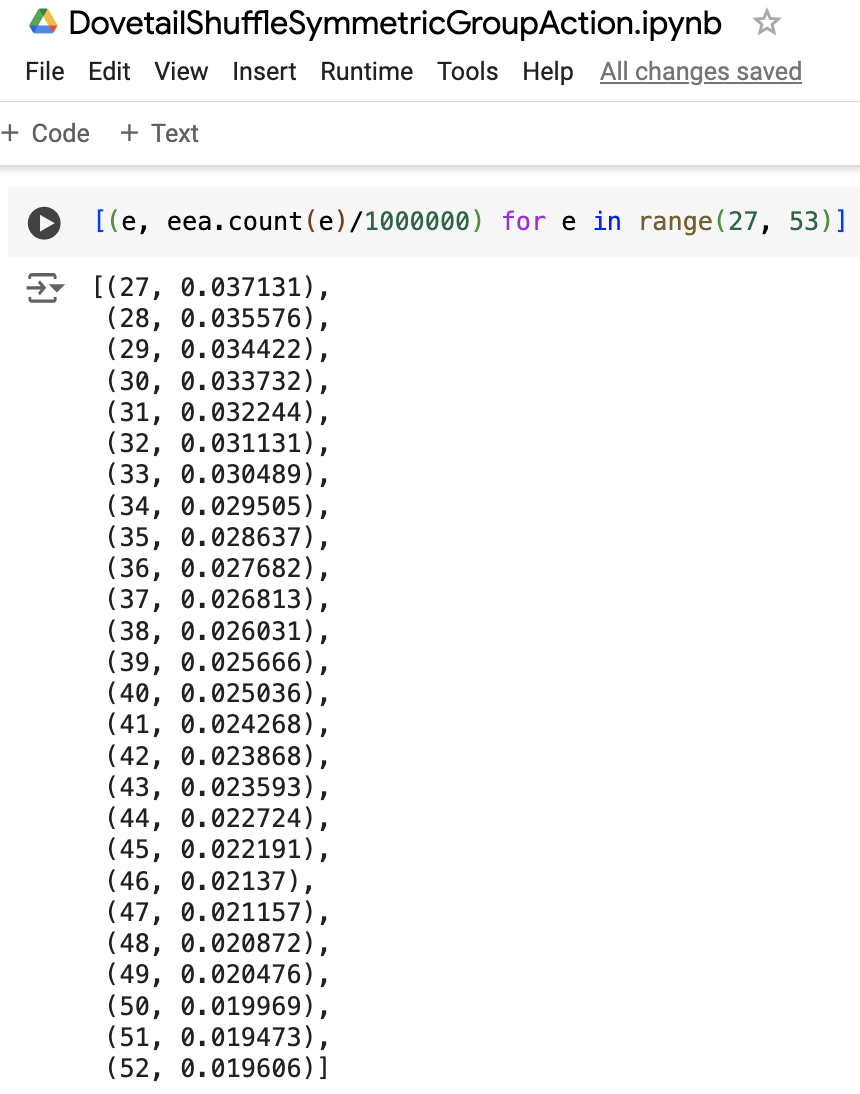

From earlier, we should remember that we can calculate the true probability of occurrence of a giant cycle in the cycle composition of a random element from the permutation group. Since the experiments were implemented using a deck of 52 cards, we are interested in the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle, which should be 27 or larger (g > 26). However, it is also important to note that we should be conducting a hypothesis test about the occurrence of giant cycles of any and all sizes. First we can conduct a hypothesis test about the probability occurrence of a giant cycle of any size, and we can calculate that this is 1/27 + 1/28 + 1/29 + … + 1/52 = 0.683. However, we can also remember that because the occurrence of a giant cycle of any size is mutually exclusive, then we can also conduct a hypothesis test with each and every single individual valid giant cycle size. Consequently, the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle of size 27 is 1/27, the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle of size 28 is 1/28 and so on.

Note, the probability of occurrence of a giant cycle of size k is always 1/k so long as the cycle is a valid giant cycle, thus k > n/2 where we are interested in the symmetric group isomorphic to the set of integers up to n [1, 2, … n].

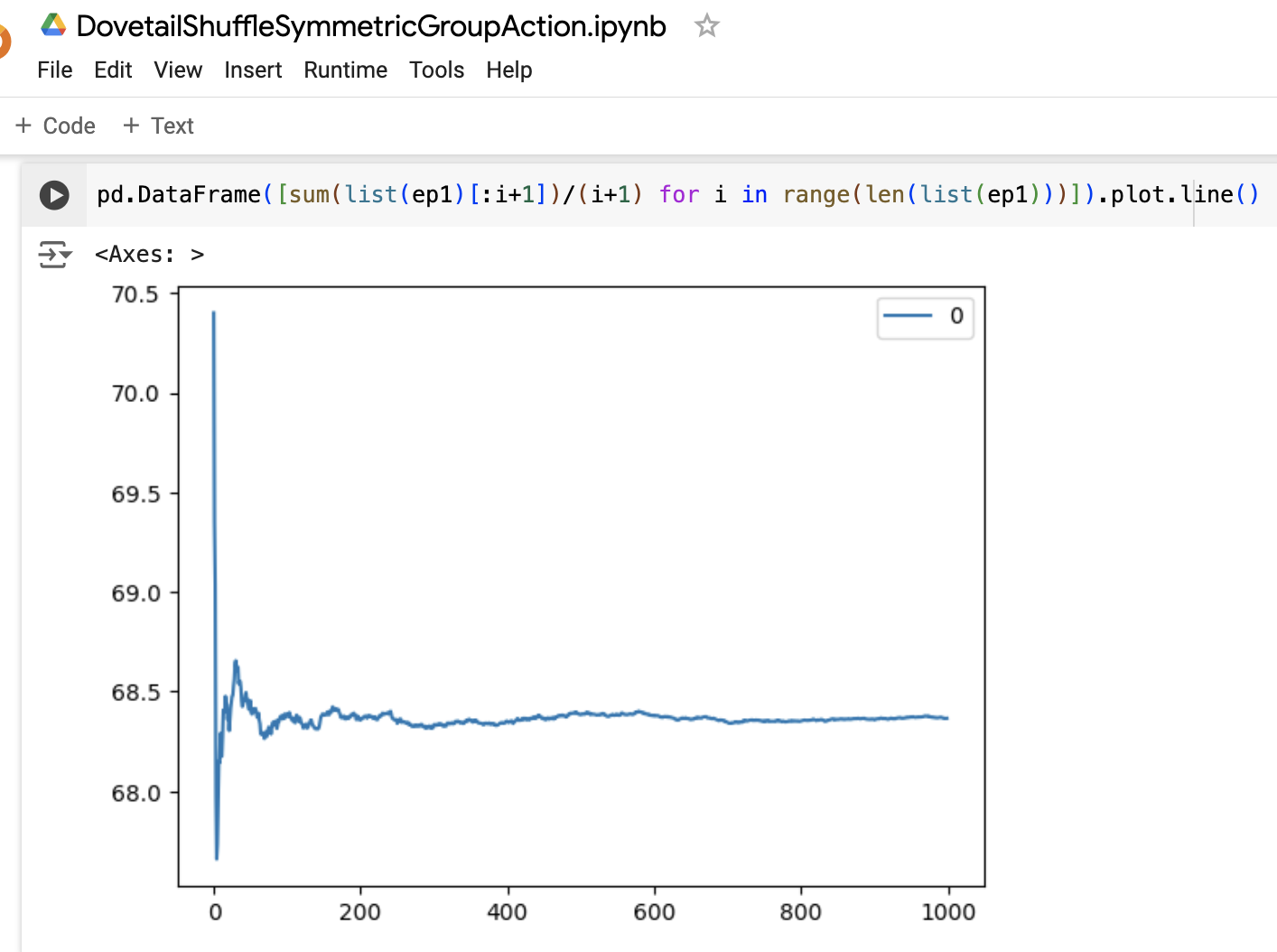

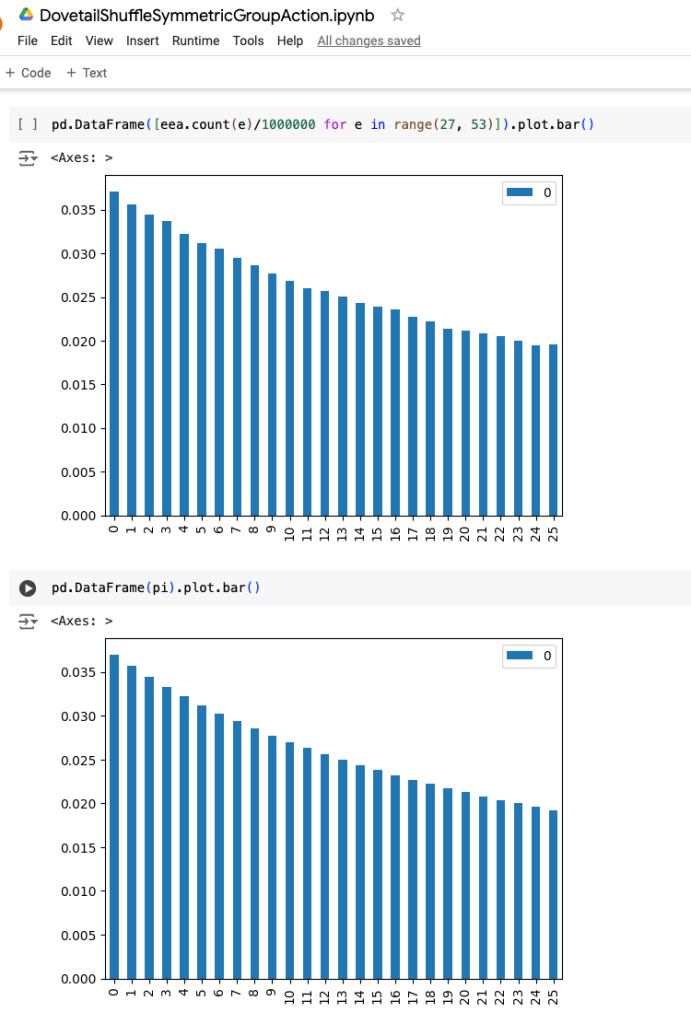

From the selections of code above, we can see that in our dovetail shuffle hoping to approximate S52 symmetric group action, the empirical probability of giant cycle occurrence was 68.366% in 1M experiments, with 683,662 event occurrences.

The code on the left above is the exact computation of the true probabilities of interest as 1/k for 26 < k < 53 and the code on the right above is the computation of sample empirical giant cycle probabilities resulting from the events in our 1M dovetail shuffle experiments. From the selections of code above, we can see that in our dovetail shuffle, the empirical probability of giant cycle occurrences do tend to match the true probability of giant cycle occurrences expected of a uniform random sample of symmetric group action permutations.

The graph below of values calculated above seems to confirm that the occurrence of individual giant cycle sizes seems to match the 1/k non-increasing trend 1/27 > 1/28 > 1/29 > … > 1/52 to be expected of the distribution of giant cycles in the uniform measure over permutations, however more detailed consideration can be taken with hypothesis testing.

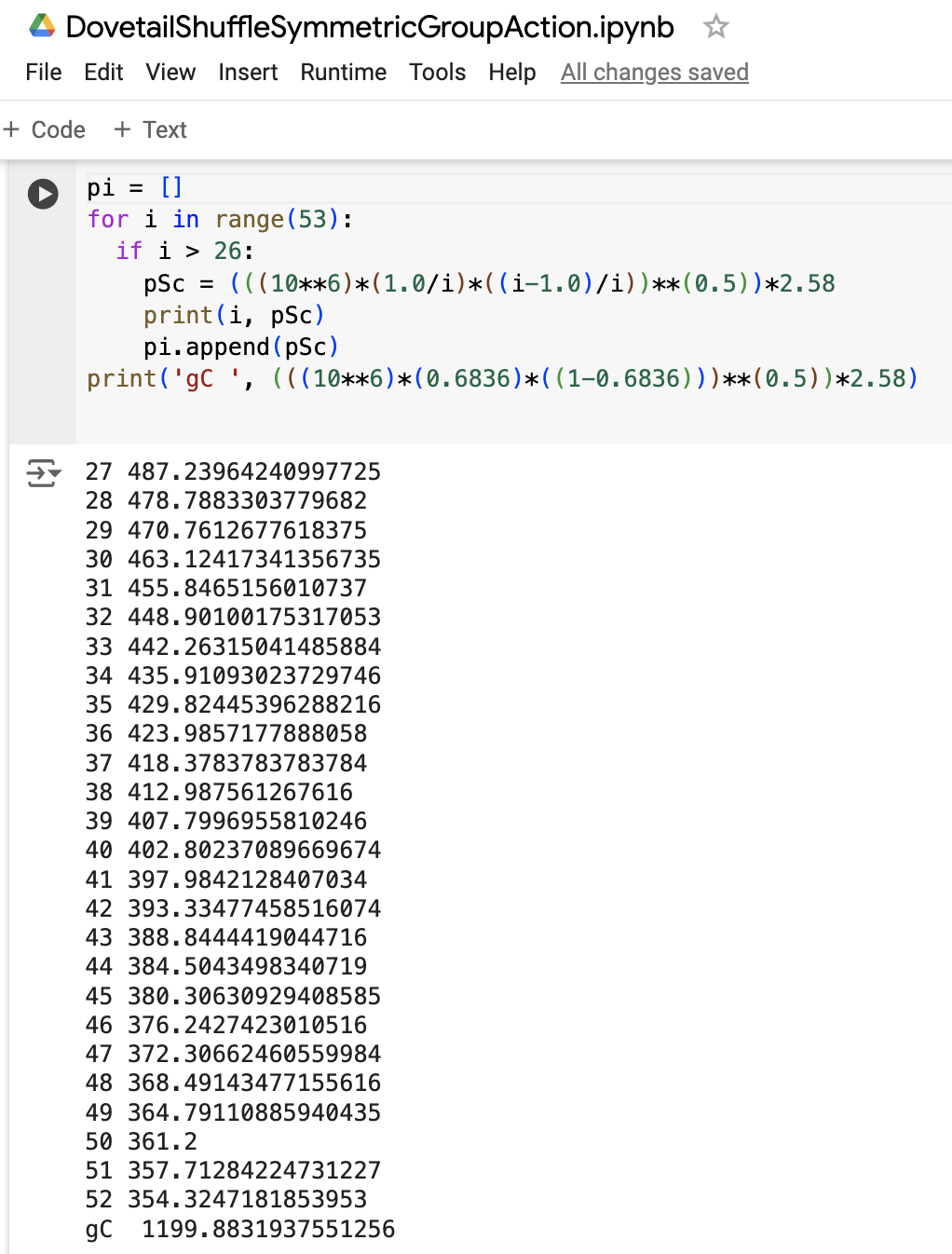

For the experiments with 1M samples from the 52! ~ 10^68 permutations, significance levels for Bernoulli hypothesis tests of the true giant cycle probabilities are difficult to calculate. Using python I was able to calculate the significance level of a hypothesis test for a 1K sample experiment with a threshold of 1 as 2.5%, meaning that an experiment of 1K samples should must have between 682 and 684 giant cycle occurrences to pass the Bernoulli hypothesis test at the 2.5% significance level, however for experiments with 10^4 samples or larger, the combinatorial considerations of Bernoulli probabilities are too large for calculations in my python notebook environment.

Nonetheless, a reasonable large sample approximation will allow us to use the CLT to conduct hypothesis tests for the 1M sample experiments at the 1% significance level.

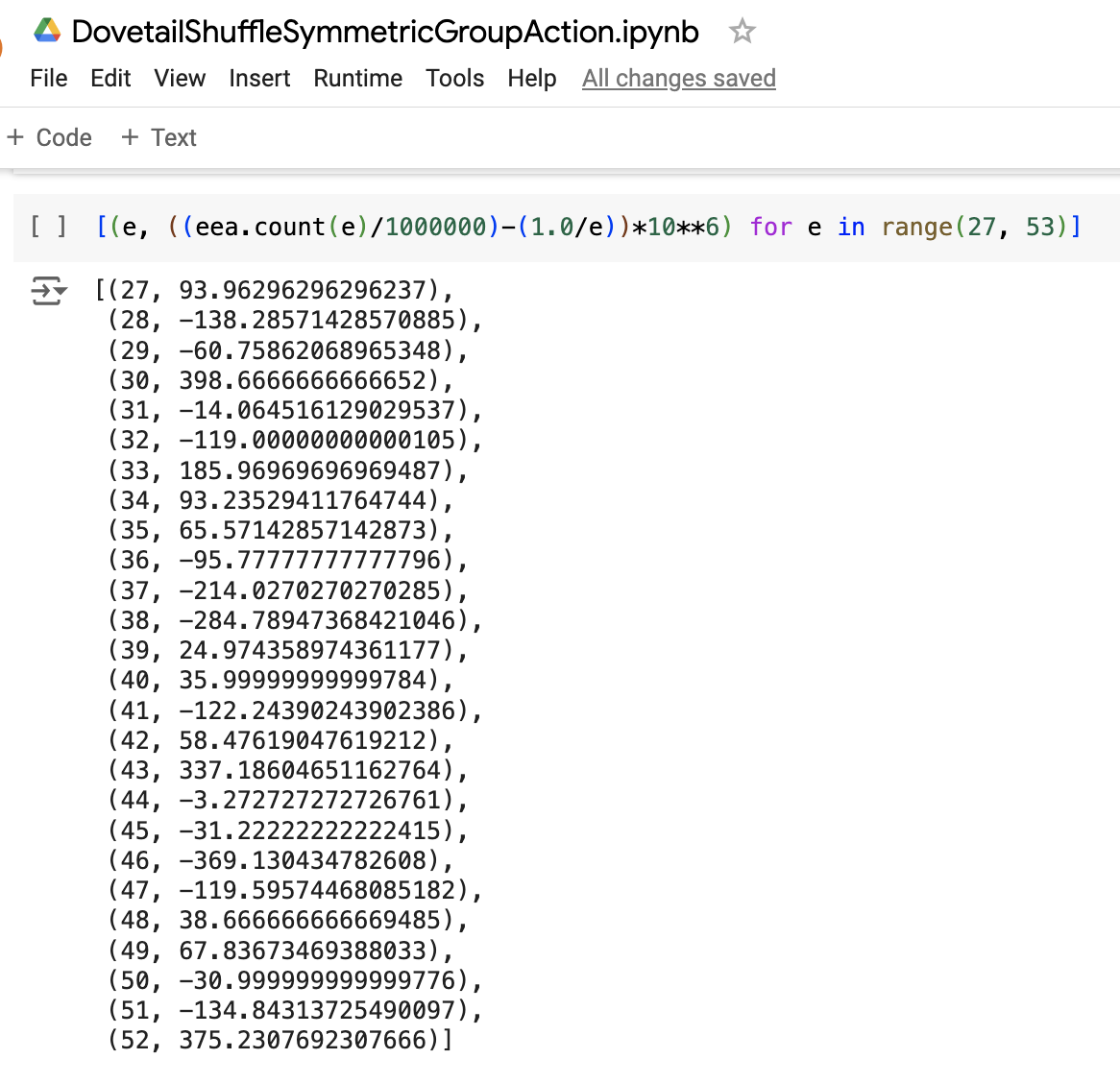

The code below on the left shows for each empirical giant cycle size occurrences how many events they were below or above expectation, and the code on the right calculates the two-sided threshold for each and every individual giant cycle size, and also the two-sided threshold for the event occurrences of any giant cycle size.

Upon inspection, we can see that all of the individual giant cycle sizes (except for the largest giant cycle size of 52) suggest that we accept the null hypotheses that the empirical probabilities match the true probabilities of an unbiased estimator of the uniform random measure over permutations.

For the giant cycle size of 52, we can see that the empirical event occurrence count was 375 events above expectation, and with our two-sided threshold of 354 events at the 1% significance level, we should reject the null hypothesis that this dovetail shuffle is an unbiased estimator of the occurrence of giant cycles of size 52. However, this is only 1 hypothesis test of the 26 possible giant cycle sizes in S52, and with various implications, the cycle size of 52 is the least probable giant cycle in S52 so there is still a good chance that the occurrence of giant cycles, regardless of size, convincingly match the true values of a uniform measure over permutations.

Here we can note that the 1,199 threshold for the occurrence of giant cycles regardless of size confirms that we accept the null hypothesis that the 683,662 event occurrences support the dovetail shuffle as an unbiased estimator of the uniform measure over permutations which would expect 683,624 event occurrences.

There are many directions that these experiments may take in the future. I believe that if a sufficiently amenable dovetail shuffling procedure is discovered, then a series of hypothesis tests of growing size (1M sample, 10M sample, 100M sample, etc.) should start a confirmation of the dovetail shuffle as an unbiased estimator of the uniform random measure over permutation group elements of S52. Of the 27 hypothesis tests conducted, 26 result in accepting the null hypothesis, and so I believe this may be a good reason to conduct hypothesis tests with larger samples to collect more information toward evaluating whether null hypotheses acceptances are convincing evidence of the dovetail shuffle as unbiased. At the moment, I believe that there is good evidence of the dovetail shuffle as unbiased estimator of the uniform random measure over permutation group elements, but the best part is that if this is latently true, then there is always more information we can collect in order to further evaluate this fact as empirically true or false.

Leave a comment