Greetings! Welcome to Agreeable Instantiations Volume 3: Random Permutations, Symmetric Group Action and The Dovetail Shuffle, Continued. In this week’s post, I hope to continue the dialogue developed in Volume 2 concerning the study of the dovetail shuffle as an unbiased estimator of the uniform measure over the permutation group elements of symmetric group action.

In Volume 2 we introduced the dovetail shuffle as a non-deterministic shuffling procedure with the potential to approximate the uniform measure over the permutation group elements of symmetric group action. Really, the dialogue is centered around a meta-hypothesis which asks whether there exists a dovetail shuffling implementation which is an unbiased estimator of the uniform measure of interest. The development of this meta-hypothesis is important—it might be even harder to develop a reasonable answer to the meta-hypothesis since there are so many sub-hypotheses that need to be addressed in order to answer the meta hypothesis on the whole, but Volume 3 will hope to build on progress made in Volume 2 toward addressing important sub-hypotheses which hold null hypotheses that the empirical values of the non-deterministic dovetail shuffle match the true values of the uniform measure over the permutation group elements.

In Volume 2, we conducted hypothesis tests to confirm that the empirical probability of occurence of giant cycles of any and all sizes match the true probability of occurence of giant cycles as implicated by their group theoretical definitions. In this week’s post we hope to again conduct a similar set of hypothesis tests, but with a different kind of implementation for our dovetail shuffle, there is hope that the new implementation will yield empirical values which provide more compelling support for the meta-hypothesis of interest.

In the original implementation of the dovetail shuffle in Volume 2, the deck is shuffled 4 times, splitting the deck into 2 or 4 blocks each time and riffling the blocks back together by randomly selecting a card from the top or bottom of a selected block. The deck is split into 2 or 4 blocks because these block sizes evenly divide the 52 card deck. This original implementation of the dovetail shuffle provided good evidence in support of the meta-hypothesis as the empirical occurrence of giant cycles of any size was well within the acceptance region of a CLT approximation -Bernoulli hypothesis test at the 1% significance level and also the empirical occurrence of giant cycles of each and every individual size were within the relevant acceptance regions of the CLT approximation-Bernoulli hypotheses tests at the 1% significance level (with an exception for the individual giant cycle size of 52, which had slightly too many empirical event occurrences to pass the CLT approximation -Bernoulli hypothesis test at the 1% significance level).

The new kind of implementation for the dovetail shuffle which will be investigated in this week’s post was initially inspired by a realization, in the original implementation we were limited by the prime factorization of 52 as the cardinality of S52. Maybe it is possible to implement a more fair dovetail shuffle by considering a deck of cards with a large cardinality whose prime factorization has much more elements. For example, by shuffling a deck of 200 cards, we can divide the deck into 2, 4, 5, 10, 20, 25, 40, 50, etc. blocks. In this way, we have a bit more optionality about how many blocks we can split the deck into and maybe this will help create a more fair dovetail shuffle implementation. Once we have a fair dovetail shuffle of 200 cards, we can take any given permutation from our dovetail shuffle of 200 cards and randomly select (200 choose 52) cards from our deck in order to yield a final shuffle of 52 cards and hopefully as a subset of a fair shuffle of 200 cards, this final shuffling of 52 cards is also a fair dovetail shuffle.

Here it is important to note that we have found two important parameters that may help make the implementation of a dovetail shuffle more fair. 1: The cardinality of the deck that we shuffle and the number of elements in its prime factorization determines the array of choices we have for a given dovetail shuffle implementation. 2: Shuffling a large deck of cards and randomly selcting a subset of those cards may help produce a more fair shuffling procedure.

With these facts in mind, in this week’s post, I was able to design a new implementation of the dovetail shuffle which first shuffles a deck of a large cardinality and then randomly selects a subset of 52 (or 26) cards/elements in order to yield a final shuffling of 52 cards which is our desired cardinality for many card games of interest. In initial experiments, it was seemingly influential to consider a deck which is a large multiple of 26. Thus, the experiments conducted for Volume 3 were conducted with decks of size 832, 416, 208, 52, and 28. In these experiments we develop an appropriate dovetail shuffling procedure for the large deck size based on the prime factorization of its cardinality and then we subsample 26 elements from the large deck in order to yield a final shuffling of 26 cards.

Importantly, we are aiming to produce a shuffing procedure for a deck of 52 cards, but it is reasonable to think that if we develop a fair shuffling procedure for 26 cards, then we can split our 52 card deck in half and fairly shuffle each half of the deck and also riffle these halves of the deck back together in order to produce a fair shuffing procedure for 52 cards. So, for the purposes of Volume 3, we will focus on developing a fair shuffing procedure for 26 cards. Also, this may help save time in the early stages of experimentation in this mini-series on the dovetail shuffle.

In this week’s Volume, the experiments were designed to conduct hypothesis tests on any and all giant cycle sizes of the dovetail shuffle of 26 cards. For each of the large deck sizes, 50 consecutive sampling experiments of 250K shuffles are tested and each experiment is uniquely classified by whether or not the empirical values of the 250K shuffles pass every hypothesis test concerning any and all giant cycle sizes. In this way, we hope to discover a dovetail shuffling procedure which, for any given experiment, is able to pass every hypothesis test concerning any and all giant cycle sizes, with high probability.

Importantly, for the deck of 26 cards, there are 13 giant cycle sizes (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26) and also the occurrence of giant cycles of any size, for a total of fourteen hypothesis tests concerning the occurrence of giant cycles. This means that with our hypothesis tests at the 1% significance level, there is a 1 – (0.99**14) = 0.13 or 13% chance that at least one of these fourteen hypothesis tests results in a rejection of the null hypothesis. And remember, in our experimental design, any single rejection of any one of the 14 null hypotheses results in a failed experiment. Thus, it seems we would like to develop a dovetail shuffling procedure which provides compelling evidence that it can yield passing experiments > 87% of the time. This is why we conduct 50 consecutive experiments for each large deck size to effectively empirically estimate its percentage of passing experiments. Hopefully, if we find a fair dovetail shuffling procedure it should be able to yield passing experiments > 87% of the time.

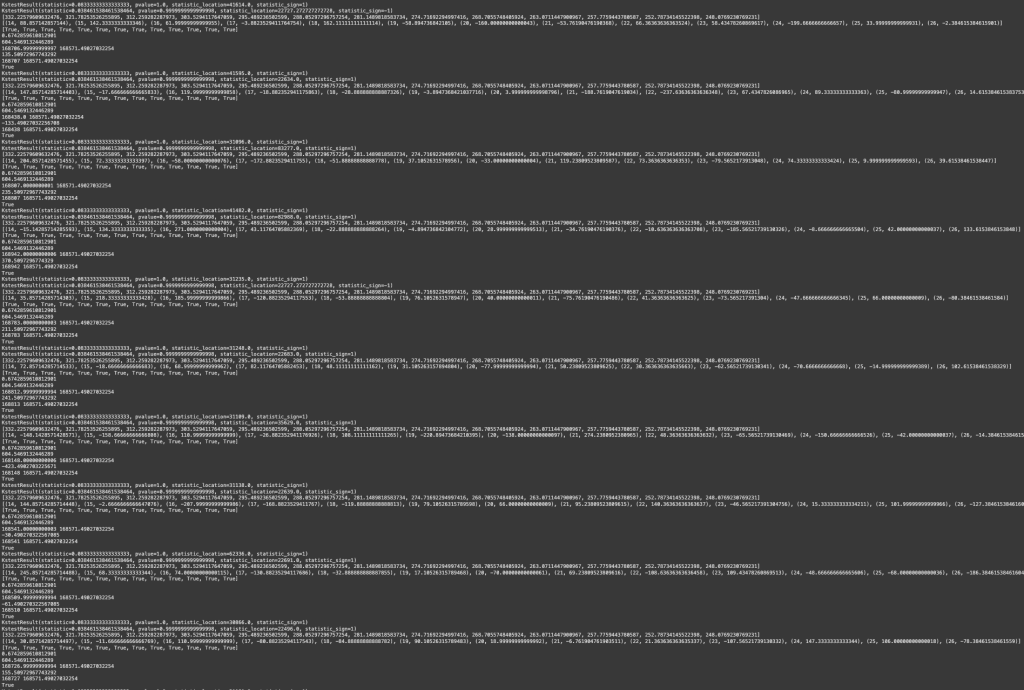

In the experiments conducted for Volume 3, the large deck size of 832 passed 48/50 experiments testing the giant cycle bias of the subsampled 26 card shuffled decks. The large deck size of 416 passed 44/50 experiments testing the giant cycle bias of the subsampled 26 card shuffled decks. The large deck size of 208 passed 42/52 experiments testing the giant cycle bias of the subsampled 26 card shuffled decks. The large deck size of 52 passed 40/50 experiments testing the giant cycle bias of the subsampled 26 card shuffled decks. And finally, the large deck size of 28 passed 0/50 experiments testing the giant cycle bias of the subsampled 26 card shuffled decks.

Consequently, it seems there is convincing evidence that the large deck size does help create a more fair dovetail shuffling procedure. Every shuffling procedure has latent bias and implementation bias. An important factor in mitigating this bias is an understanding how the entropy of random selections made by the shuffling algorithm is translated into algorithm’s yielded entropy over the permutation group elements. As the cardinality of the permutation group elements is n! and the uniform measure over these permutation group elements is the maximal entropy distribution of cardinality n!, it is important to make sure that the translation of entropy is efficient.

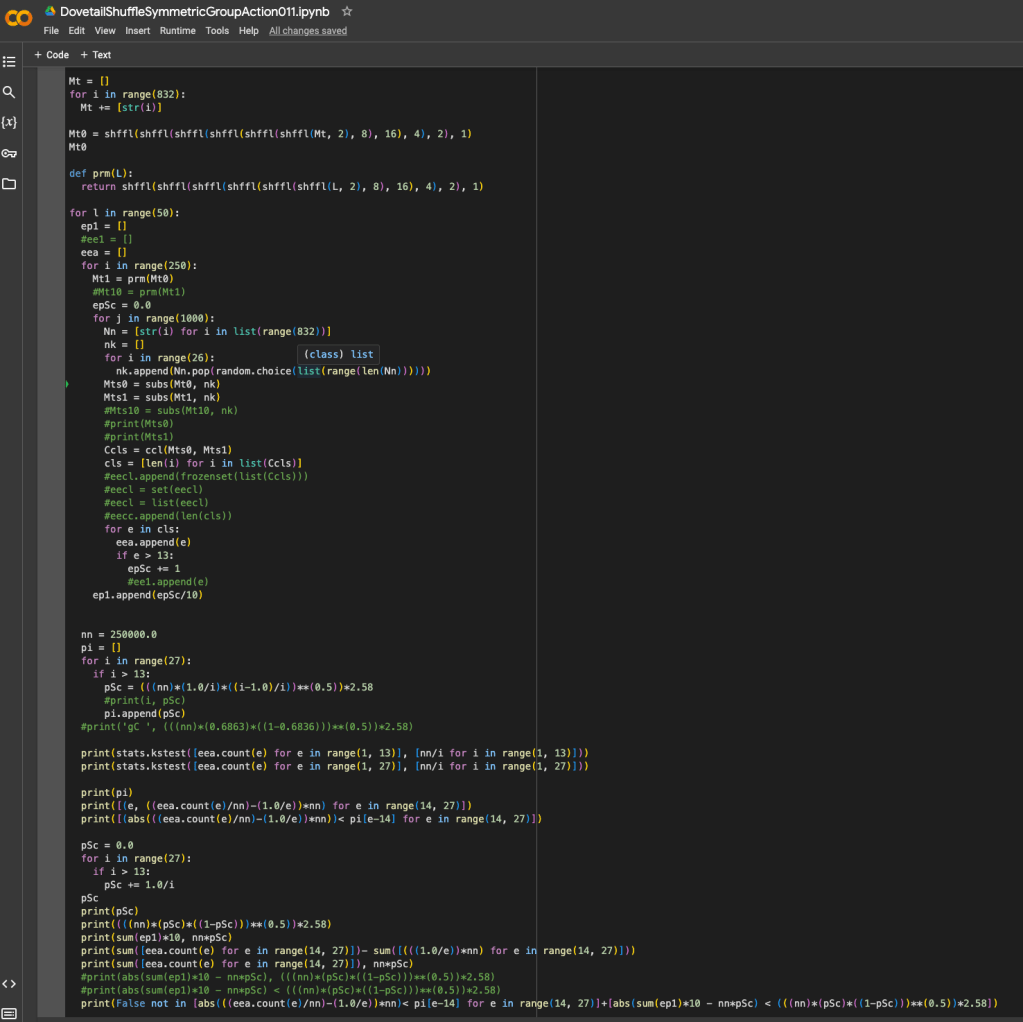

From the code selection below, we can note that for the 832 card large deck size, we defined our permutation procedure to shuffle the deck 12 times, dividing the deck into 2, 8, 16, 4, 2 or 1 block each time and riffling these blocks back together. Importantly, as (832 choose 26) ~ 10**49, the code only shuffles the 832 card deck 250 times, and from this one shuffle it is relatively straightforward to subsample 1000 different combinations of 26 cards to produce unique shuffles of the 26 card deck for a total of 250K 26 card shuffled decks. Thus, we are able to create a fair dovetail shuffling procedure by shuffling a relatively large 832 card deck with a large number of elements in its prime factorization which are the potential number of blocks in any given step in the implementation of the permutation procedure, and we can make this shuffling procedure even more fair by taking a subsample of 26 cards. At the very least it does seem that we have achieved the efficient entropy translation we hoped for with the large deck subsample, however more investigation may be needed to explain exactly why and how.

The code for the 832 card large deck size and also the results of the first 10 experiments are shown below for reference.

Leave a comment